|

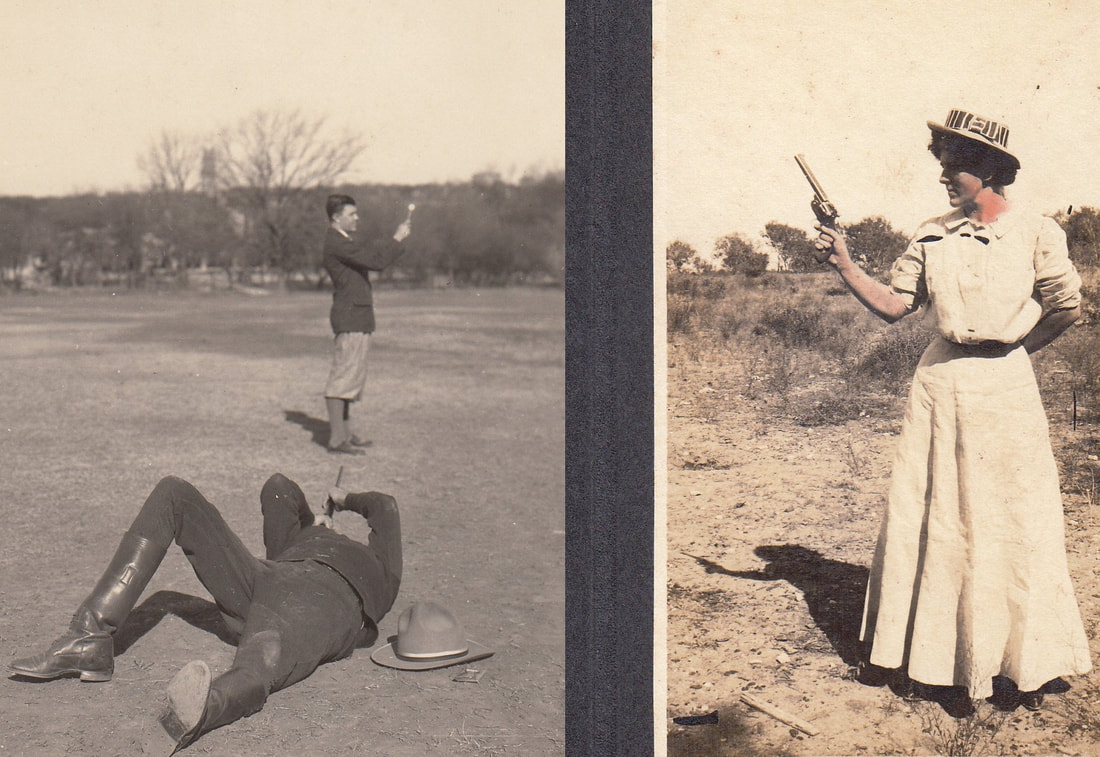

People have had a long fascination with trick shots. From early horse archers displaying impossible feats to today when “Dude Perfect” videos receive millions of views online. Watching people execute amazing displays of accuracy, stamina and, well, perfection has always been an exciting form of entertainment. That has never been more apparent than during the late 1800 and early 1900s. During this time vaudeville acts would routinely employ marksmen as a part of the show. In their largest form, exhibition shooting would be associated with travelling acts, such as, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show featuring household names like Annie Oakley. However, a husband and wife team with roots in Texas was easily the most accomplished. The Beginning On October 16, 1869, Adolph ‘Ad’ Toepperwein was born in Boerne, Texas. Ad was the son of German immigrants and his father, Ferdinand, was a renowned gunsmith who would establish a shop in Leon Springs shortly after Ad’s birth. Ferdinand quickly introduced Ad to firearms, giving him a cross bow at six and then a 14-gauge shotgun at age eight. By the time he was ten, Ad was already the equal of most grown men when it came to handling and performing with firearms. However, all wasn’t a happy childhood for young Ad; he would lose his father when he was just 13. Shortly before his death, Ferdinand gave Ad a .22 single shot rifle. Ad spent so much time with the .22 it became an extension of his self. As Ad’s fascination and ability with firearms grew, he became familiar with the stories of Doc Carver. Impressed by Carver’s amazing feats, Ad went to see him perform. The performance was so impressive, Ad immediately decided he wanted to become an exhibition shooter. Ad’s early career was unassuming enough. His first job was at a crockery shop in San Antonio where he spent most of his time dusting the merchandise. Bored with such a menial job, Ad finally quit. His next job, while still having nothing to do with shooting, would play an important role later in Ad’s life. After leaving the crockery, Ad joined the staff of the San Antonio Express News as a cartoonist. The Start of a National Career As a side gig, Ad performed as local act at one of San Antonio’s theaters. The theater’s manager was impressed with Ad’s talent and decided to make an investment in young Ad. So, just before turning 20, with the manager’s backing, Ad made a trip to New York in an attempt to join the vaudeville circuit. While many vaudeville producers dismissed the “Texas Triggerman” as just another routine act with no special talent, Ad and his manager had a stroke of marketing genius – the pair set up a trip with a booking agent for the B. F. Keith vaudeville circuit to join them on an all-expenses-paid journey to Coney Island. Once there, Ad proceeded to blow through targets at shooting gallery after shooting gallery. While most of his targets were plaster birds or stars, one gallery had a special promotion where a ¾ inch bulls-eye 30 feet away would cause a bell to ring. Every time a shooter caused the bell to ring, they would receive a free 10-cent cigar. Ad rang the bell until the proprietor was out. He also smashed every target on display without missing. Soon a crowd gathered to observe and cheer Ad on. Once he had fully cleared the first gallery, he moved on to a second methodically clearing the targets there and drawing an even larger crowd. As the other galleries on Coney Island heard about the young marksman, they closed their doors for the day. It was such a sensation, the next morning the New York World ran a story about, “The boy from Texas who put shooting galleries out of business at Coney Island.” The agent from the Keith Circuit was more than impressed and signed Ad to a contract for $70 a week, launching Toepperwein’s professional career. While there were plenty of other shooting acts at vaudeville shows, Ad quickly found a signature performance that separated him from the pack. Utilizing skills learned from his time as a cartoonist, Ad would end shows by using shots to punch holes in a tin sheet to create pictures. From Popeye to Uncle Sam, Ad was capable of drawing nearly anything with bullet holes, but he was most famous for his Indian chief drawings. While some of these art pieces were simplistic, others were incredibly intricate, including one where he used over 450 shots to depict a Sioux Indian chief in full war dress – the entire effort took Ad a mere twelve minutes. After two years on the vaudeville circuit, Ad was lured to work for the Orrin Brothers Circus which took him through nearly every state in the country and Mexico. Twice, while south of the border, Ad’s shooting indirectly caused “miracles.” The more famous of the two miracles involved a bet from a fellow circus troupe member. He told Ad he couldn’t hit the bell in what looked like an abandoned mission, far on the horizon. Ad quickly took him up on the bet. While Ad’s first shot missed, he reloaded, readjusted and struck the bell with his second shot. He followed this up with four more direct hits on the bell. Unknown to Ad, the poor parishioners of the mission had been unable to afford a new clapper for the bell so it had sat silent for many years. When they heard the bell begin miraculously ringing, the town erupted and news traveled quickly. Within days a large revival sprung up at the site and pilgrimages were formed to visit the mission. Thanks to all of the attention, the mission received much needed financial aid. Ad began to grow weary of the repetition and monotony of his circus performances, so when, in 1901, he was offered a position with the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, he gladly accepted. Ad joins Winchester Ad’s move to Winchester would change his life in more ways than one. The agreement would begin a fifty-year partnership between Winchester and Ad, allowing a free and creative environment that would really let Ad’s exhibitions shine. Perhaps even more importantly, during a tour of Winchester’s New Haven plant in 1902, Ad was struck by a young girl working a cartridge loading machine. Ad demanded the foreman introduce them – her name was Elizabeth Servaty. Even while away, Ad remained in constant contact with Elizabeth and, in January 1903, he returned to New Haven to marry her. Elizabeth came with Ad to San Antonio where his family took an immediate liking to her. During this time period, it was rare for women to use firearms, much less compete or participate in exhibitions. However, shortly after their return to San Antonio, Elizabeth told Ad she wanted to learn to shoot. She knew Ad would be away from home for long periods due to his exhibitions and, if she learned to shoot, she might be able to find a role with him on the road. While Elizabeth had worked for Winchester for years, she had never actually fired a gun. Ad decided to start her out with the gun that had inspired him in the first place – a .22. After just one month of practice, Elizabeth was shooting chalk and crayons out of Ad’s lips and outstretched fingers. She would place ten shots into such a tight grouping the hole they created could be covered by a nickel. Elizabeth was such a great student that Ad quickly moved her from stationery to aerial targets. Again Elizabeth was a quick learner, knocking any size tin can out of the sky. Elizabeth would always describe the sound of bullets hitting cans as “plinking,” something that Ad found endearing. Soon he would start calling her Plinky, a name that would follow her for the rest of her life. Now with an accomplished partner, the duo became an even bigger draw. For 42 years, the couple traveled the United States, Canada and Mexico becoming one of the most well-known international spectacles at the time. They were billed as, “The Fabulous Topperweins” (the first ‘E’ was removed from their last name as an attempt at Americanization). The Legend Grows When the Toepperweins came to town everything would shut down. In one case, the duo put on an exhibition in an east Texas town the same weekend as a prolific murder trial. When it was announced there was no way for the Toepperweins to delay the show, the judge quickly adjourned the court until ten o’clock the next morning. As Plinky and Ad lined up on a baseball diamond in the center of town, the judge, jury and every spectator from the court case were in attendance. However, it wasn’t just their popularity that made the Toepperweins so amazing – they were genuinely great shots. The 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis was the first major benchmark for both Ad and Plinky. Over a three day exhibition, Ad would score 19,999 hits out of a possible 20,000. It was his first official record. Meanwhile, Plinky, not to be outdone, established her first world record when she hit 967 of 1,000 thrown clay discs – the best mark ever for a female shooter. Ad’s most well-known record occurred between December 13th and the 22nd in 1907. Back in San Antonio, Ad would be attempting to break the highest scoring mark. This was Ad’s biggest goal from the beginning of his career. When Ad finally attempted to break the record, it stood at 59,720 composition balls. That record was set by Captain Bartlett in 1889. As Ad began his attempt, he had 60,000 white pine wooden blocks ready to go. At nine o’clock on the 13th, Ad took his first shot. Over the course of the next 10 days, he would shoot at 72,500 targets, only missing nine. Twice, on the 17th and the 21st, Ad hit 8,000 targets without missing. His worst day was the 20th, when poor weather led to Ad missing four of his 7,000 shots. The feat required Ad to rotate his gun every 500 shots due to the barrel overheating. By the time he was done, every available round of ammunition in San Antonio was gone. Even if there had been more ammo, Ad’s body was too exhausted to go on. During his 10th and final day, Ad actually began to black out but was saved from falling when one of the boys throwing targets grabbed him. Plinky would subject herself to such grueling feats of stamina as well. In 1916, Plinky would make a run at 2,000 straight targets during an event in Montgomery, Alabama. Over the first 1,000 shots, a severe blister formed over Plinky’s hand. She was forced to stop momentarily when the blister broke open. A doctor came and treated her but she went right back to shooting. After about a dozen more shots, Plinky ripped the bandage off due to it interfering with her shooting. She finished the event with a bare and bloody hand, hitting 1,952 of the 2,000 targets. Even with the injury, she actually shot better in her second 1,000 rounds than she did in her first. The Toepperweins set many records during their career. People enjoyed watching them accomplish more and more outrageous feats. Once, Ad tossed washers into the air shooting bullets through their center hole. When a spectator questioned the veracity of the shot, Ad wrapped the washers in paper, shooting straight through the middle. In many aspects, Ad was an all-around athlete. He was described as, “…more than six feet tall and as agile as a circus acrobat.” However, when asked who the better marksman was Ad would grin and respond, “Well, like the booklet says, I was the best at some feats. She was the best at others. Reckon it was a toss-up between us.” What isn’t in doubt is that Plinky was the greatest all-around female marksman ever. While you might find an individual who was a better rifleman than Plinky, Plinky would undoubtedly be better with a pistol and a shotgun (or vice versa). Plinky was the first woman ever to achieve a perfect score at clay pigeons. She would score that perfect 100, 197 times during competition. During their travels, Plinky would challenge the four best shooters at local gun clubs to a competition. Each man would shoot 25 targets and then pass it to the next shooter. They would add their four scores and post it against Plinky’s full 100. Even though the men’s shots required less stamina and focus, Plinky would almost always win, even when the gentlemen were excellent shots themselves. For example, once the men shot scores of 24, 25, 25 and 23 for a total of 96. Plinky didn’t break a sweat. She casually scored a 99, only missing her 91st shot. During World War II, Ad and Plinky did what they could to support the war effort. They did exhibitions in front of hundreds of thousands of soldiers during their basic training courses across America. Even though Ad was now in his seventies and Plinky was only 11 years his junior, they maintained the high standards they achieved throughout their career. Ad would continue to do a shot that required him to run and do three somersaults before shooting targets out of the air. In 1945, the strain of a hectic, but fulfilling, life caught up to Plinky as she suffered a heart attack and passed away. Ad took Plinky’s passing extraordinarily hard, but he remained active in the shooting community, both for support and as a way to remain connected to his soul mate. Into Retirement In 1951, Ad officially retired. He setup a shooting camp in Leon Springs that provided free weekend classes for youths, young business men, soldiers from the nearby bases in San Antonio and anyone who was interested in sport rifle and pistol shooting. Ad would finally pass away himself in 1962 at the age of 93. When looking back on his career, Ad said, “I’d do it all over again if I had the chance, but this time around I would stress even more the importance – the vital importance – of every American boy owning a rifle and knowing how to handle it. Working with Winchester as an exhibition marksman brought me all I ever wanted – a wonderful life, a wonderful wife, the world’s rifle shooting championship, travel, good friends and a good living.” Written by Ryan Sprayberry, Collections and Exhibits Manager at the Texas Sports Hall of Fame

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

November 2023

Categories |

Contact1108 S. University Parks Dr.

Waco, Texas 76706 |

© Texas Sports Hall of Fame. 501(c)(3). All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed