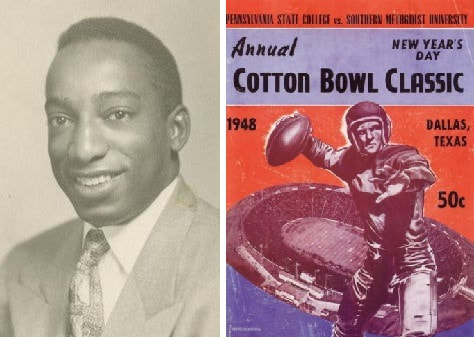

While the state boasts many colorful and entertaining bowl games today, there are two that hold a special place in the state’s history. First, there is the Sun Bowl which is tied for second-oldest bowl game in the country (with the Sugar Bowl and Orange Bowl, behind only the Rose Bowl). The Sun Bowl was first played in 1935 and has held a game in El Paso every year since. The second Texas bowl game was inspired by Southern Methodist University’s 1936 trip to the Rose Bowl. Impressed with the pageantry and fanfare, Texas oilman, J. Curtis Sanford, organized the first Cotton Bowl in 1937. Since that time, the Cotton Bowl has built an illustrious history culminating with its inclusion in the rotation of bowl games used in the College Football Playoff system in 2015. However, like the state, these two storied institutions struggled with the issue of racial equality and inclusion. The Sun Bowl did not face the issue of segregation until its 15th edition. When selecting a visiting team for the 1949 contest, the selection committee offered an invitation to Lafayette College in Pennsylvania. However, the Sun Bowl was played on the Texas College of Mines’ campus, placing the game under the rules and restrictions of the University of Texas system which forbade interracial play. When the Sun Bowl selection committee was made aware of the fact that Lafayette halfback, Dave Showell, was African American, they informed the Lafayette president that Showell would not be able to participate in the game. Despite frustration with the exclusionist policy, Showell, a popular World War II veteran who served as a Tuskegee Airman, urged his teammates to play. After all, this was Lafayette’s first major bowl invitation. With Showell’s approval, the football team and athletic council voted to accept the Sun Bowl’s invitation, sending the offer to the school’s faculty for final approval. In an unexpected turn, the faculty overwhelmingly voted against accepting the Sun Bowl invitation, largely due to the Sun Bowl’s racial restrictions. Lafayette’s student body, all-male at the time, erupted in protest against the faculty vote. Nearly 1,500 students marched on the president’s house in demonstration. When Lafayette President, Ralph C. Hutchinson, stepped out to inform the students the faculty decision was due to the racial exclusion, the students turned their march to downtown Easton where they held an impromptu rally against racial intolerance. Sun Bowl officials would get West Virginia University to replace Lafayette in the Sun Bowl, but they took a major hit in the press. Papers across the country, including major publications like, The New York Times, covered the story. To make the embarrassment worse, the majority of students at the Texas College of Mines opposed the ban and influential citizens of El Paso began to question why other games in the state could be integrated while the Sun Bowl was not. Under continuous pressure from the College of Mines, Sun Bowl officials and the citizens of El Paso, the University of Texas Board of Regents finally passed an exemption of the racial ban for the school and its facilities on October 27, 1950. A year later, following the 1951 football season, the Sun Bowl hosted its first integrated game with Texas Tech playing the College of the Pacific on January 1, 1952. The Cotton Bowl also faced the issue of segregation in the 1940s, although its transition went much differently than the Sun Bowl’s. Following the 1947 college football season, Cotton Bowl officials and Dallas citizens were ecstatic when Doak Walker led hometown SMU to the SWC title, guaranteeing the Ponies a spot in the 1948 Cotton Bowl Classic. Officials were even more excited when the opportunity arose for the Cotton Bowl to invite the Penn State Nittany Lions to play SMU. SMU had gone 8-0-1, finishing the season ranked third by the AP Poll. Penn State had also gone undefeated, finishing fourth in the AP Poll. This would allow the Cotton Bowl Classic to showcase the nation’s third best team playing its fourth best team. Cotton Bowl officials knew this would allow Dallas to host, “the top attraction on New Year’s Day” and bring unprecedented success to the bowl game. The only issue Cotton Bowl officials faced was the presence of two African American players on the Penn State squad: fullback Wallace Triplett and end Dennis Hoggard. Furthermore, Penn State had made it very clear over previous seasons that it would, under no circumstances, accept an invitation to a game that had policies of racial exclusion. Making a bold move for the time, Cotton Bowl officials extended an invitation to Penn State. Penn State accepted the invitation but quickly brought up the question of segregated hotels. Cotton Bowl officials could be forward-thinking in their inclusion of African American participants in the bowl game, but they didn’t have control over hotel owners. Using quick and clever thinking, the Cotton Bowl officials arranged housing for the entire Penn State team at the Dallas Naval Air Station near Grand Prairie and only about 14 miles from downtown Dallas. For the postgame awards banquet, Cotton Bowl officials did flex some muscle and utilize connections to persuade a downtown hotel to break local racial standards and allow Triplett and Hoggard to attend. The 1948 Cotton Bowl Classic was a huge success. During the first four days of mail sales, the Cotton Bowl received over 100,000 ticket applications. On the field, the game was everything it promised it would be. SMU jumped to an early lead before Penn State tied the game 13-13 in the third quarter. In the waning moments, Penn State made a final drive deep into SMU territory. As time expired, the game-winning touchdown slipped off the fingers of Dennis Hoggard in the SMU endzone, leaving the game a 13-13 tie. Afterward, the Christian Science Monitor had some bold remarks to make about the game. The Monitor argued the integrated game, “carrie[d] more significance than a Supreme Court decision against Jim Crow or a Federal Fair Employment Practices Act.” Realistically, the game did open new doors and possibilities for inclusion while allowing the Cotton Bowl to raise funds to immediately expand stadium seating to 67,000. For further contextual information, here are the other major bowl games, their dates of integration, the teams involved and the individuals who integrated the games: Rose Bowl: January 1, 1916 Brown v Washington State Fritz Pollard (Brown) Orange Bowl: January 1, 1955 Duke v Nebraska Two Nebraska players Sugar Bowl: January 2, 1956 Georgia Tech v Pitt Bobby Grier (Pitt)

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

November 2023

Categories |

Contact1108 S. University Parks Dr.

Waco, Texas 76706 |

© Texas Sports Hall of Fame. 501(c)(3). All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed