|

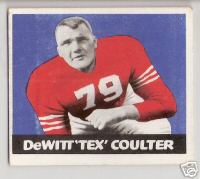

The all-time area high school football player is a gentle giant of 59 now. He's a man whose talents ranged far beyond the playing field-- an artist, cartoonist, sportswriter, builder and humanitarian. He's better known as Tex Coulter to fans across two nations who followed his later exploits with Army's powerhouse teams of World War II, the New York Giants of the National Football League and the Montreal Alouettes of the Canadian Football League. But, as Masonic Home in the late 1930's and early 40's he was Dewitt Coulter, a gifted athlete whose normal position was tackle but could play anywhere he was needed. "Those were wonderful years," said Coulter. "Masonic Home played a tremendous role in my life. I enjoyed my high school football career more than any other. That's why I'm, really thrilled by this selection." Coulter was 5 when he moved to the home with his brother and two sisters from the Red Springs community near Tyler. Their late father was a Mason, which qualified them to live at the Fort Worth home until they graduated from high school. By the time Coulter was in the seventh grade, coach Rusty Russell knew he had two rising stars in Dewitt and his older brother Ray, an end. "Whatever Rusty said, we did," said Dewitt. "We never had many players but we believed we could hold down our own against the biggest school. It was exciting to run those trick plays Rusty taught us and play a lot of different positions. Masonic Home guys always have been close. When you spend that much time together, you're brothers for the rest of your lives." Russell coached all sports at the school, so he informed all his football players they must report for track in the spring. "I talked him into letting me throw the shot while everybody else got hot running." Coulter said, "It was a nice bit of exercise." It certainly was. Coulter set a national high school record with the 12-pound shot tossing it 59 feet, 1-1/2 inches. But nothing he did surprised Russell. "When Dewitt was in the seventh grade, he pulled up crossties from an abandoned Interban line. He lifted them like weights using them to develop his wrists and fingers for the shot put. We were on a very tight budget and had only one shot put, but he persuaded me to let him keep it in his room so he could toss it from one hand to another at night." Coulter grew to 6'-5" and 200 in high school, then filled out to 240 at West Point, where he signed shortly after he entered the Army. He played on those fabled Cadet teams of the Doc Blanchard, Glenn David era, then moved into pro football with the Giants. "The 1946 Giants played for the NFL title," he said. "I thought we had better material at West Point. There was so much talent there that I was strictly a tackle.' At Masonic Home, he had played all line and backfield positions as needed and punted, too. Later with the Giants, where his teammates included another young Texan named Tom Landry, he was an offensive and defensive end, offensive and defensive tackle, linebacker and punter. As a pro, Coulter grew to 265, but his boyhood fondness for cartooning lured him into retirement in 1950. He joined the sports staff of the Dallas Times Herald and spent a year turning out delightful cartoons. He was a familiar figure in Southwest Conference press boxes, frequently turning to his typewriter to write a story when his art work was finished. "I really enjoyed that," he said. "If I had been older, I probably would still be doing it. But I didn't have football out of my system. When the Giants came to Dallas in the summer of '51 to play an exhibition game with the Detroit Lions, I decided I wanted to play again. I suited up and played most of the game in the Cotton Bowl." Coulter played five more seasons with the Giants, then moved into the Canadian League. When his playing days were over, he and his family remained in Montreal and he became one of Canada's top portrait painters. But after more than 20 years north of the border, Texas called him home. He moved to Austin, spent a few years in the home building business, then decided to devote his time to the Marbridge Foundation, located in the country south of Austin. "We're a private, self sustaining group that works with retarded persons," he said. "We grow our own food and meat, do all the cleaning and laundry. We pass out medicine and write letters for these people, just to try to give them a little better life." For Dewitt Coulter, the rewards of Masonic Home still are paying off.

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

November 2023

Categories |

Contact1108 S. University Parks Dr.

Waco, Texas 76706 |

© Texas Sports Hall of Fame. 501(c)(3). All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed